COP27: Climate Finance for Developing Countries is not Just Equitable, it is Self-Interest

Tobias Adrian, Patrick Bolton & Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis (2022)

Executive Summary

Equity considerations have been a core rationale behind the pledge to provide $100 billion a year in climate finance to developing countries. The argument typically runs as follows: (1) developed countries have historically emitted more carbon, so bear a larger responsibility for the adverse impacts of climate change; and (2) developed countries are wealthier than developing countries, so must help poor countries with climate mitigation and adaptation. In the run-up to COP27, the call to offer compensation finance for “loss and damage’’ has become especially prominent. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres put it at the opening of COP27: “Loss and damage can no longer be swept under the rug. It is a moral imperative.”

While such equity considerations matter profoundly, they have so far, however, not proved to be a strong impetus for action, as the difficulties of garnering a mere $100 billion a year in climate finance for developing countries have demonstrated. Once one takes account of the benefits to each country from emission reductions brought about by replacing fossil fuels with renewables anywhere in the world, there is a much more direct impetus for action: self-interest! Indeed, the Coase theorem states that it is in the economic interests of a country A to pay a polluting country B to stop polluting if that makes country A better off. From a Coasian perspective, it is thus sound economic logic to pay polluters for the costs of replacing fossil fuels with renewables, if the benefits exceed the cost. Indeed, Coase provides a new perspective on and rationale for (foreign transfers of) climate finance. Tangible net benefits can be reaped even if only a coalition of the willing (e.g. a region) strikes a Coasian deal to phase out of fossil fuels. The larger the climate club in terms of the emissions it can avoid, the closer the net benefits of such a deal get to the large net benefits in a global deal to get rid of fossil fuels.

Big picture, our conceptual contribution is that paying the polluter – via climate finance – to stop polluting (as is happening now, for example, in South Africa) results in a Coasian bargain. Coase won the Nobel prize for his insight that paying the polluter to stop polluting may make you better off. But, to the best of our knowledge, no work has linked his theory to the idea that the provision of climate finance could result in a Coasian bargain. No work has quantified whether such a bargain exists. Our empirical contribution it to provide the first quantification of the costs of climate finance to end coal and the net benefits this brings to different countries.

Podcast: The Great Carbon Arbitrage

Patrick Bolton & Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis (Nov 18, 2022)

Executive Summary

What is the net benefit of phasing out coal and replacing it with renewables? $85 trillion, according to a new calculation. Alissa Kleinnijenhuis and Patrick Bolton tell Tim Phillips how they estimated this extraordinary number, how the benefit can be realised – and whether the negotiations at COP27 will get us there.

How Replacing Coal With Renewable Energy Could Pay For Itself

Tobias Adrian, Patrick Bolton & Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis (2022)

Executive Summary

The world may gain an estimated $78 trillion over coming decades by making this energy transition.

The Great Carbon Arbitrage

Tobias Adrian, Patrick Bolton & Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis (2022)

Abstract

Attempts to phase out coal have faltered amid fears that the transition to renewable energy would be too costly. By comparing the present value of avoided emissions with the present costs of replacing coal with renewable energy, this column estimates that the world can realise a net gain of $77.89 trillion by shifting to renewable energy. The benefits from ending coal are so large that carbon pricing and the other financing policies discussed here merit sustained attention.

The Cost of Delayed Climate Action for the Financial Sector

Moritz Baer, Jacob Kastl, Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis, Jakob Thomae & Ben Caldecott (2021)

Executive Summary

In this report we attempt to estimate the additional cost for the financial sector that arises when climate action is delayed. We model the impact on the equity value and the probability of default for non-financial corporations (NFCs) to estimate the additional expected financial losses from transition-related increases in market and credit risk.

Analysed firms in climate-critical sectors are insufficiently aligned with the net-zero transition, highlighting that even an early transition in 2026 is likely to be disorderly, with the overall expected loss for FIs amounting to US$ 2.15 trillion. NFCs continue to build out carbon-intensive production over the next years, while insufficiently shifting towards more sustainable technologies. This results in a growing misalignment with decarbonisation scenarios and increases the financial risk build-up for exposed FIs through an increased market and credit risk.

For every year the transition is further delayed, the cost for financial institutions (FIs) increases by US$150 billion due to climate transition-related changes in market and credit risk. This represents a mean increase of financial cost per year of nearly 7% from delayed climate action.

Usable Bank Capital

Alissa M. Kleinnijenhuis, Laura Kodres & Thom Wetzer (2020)

Abstract

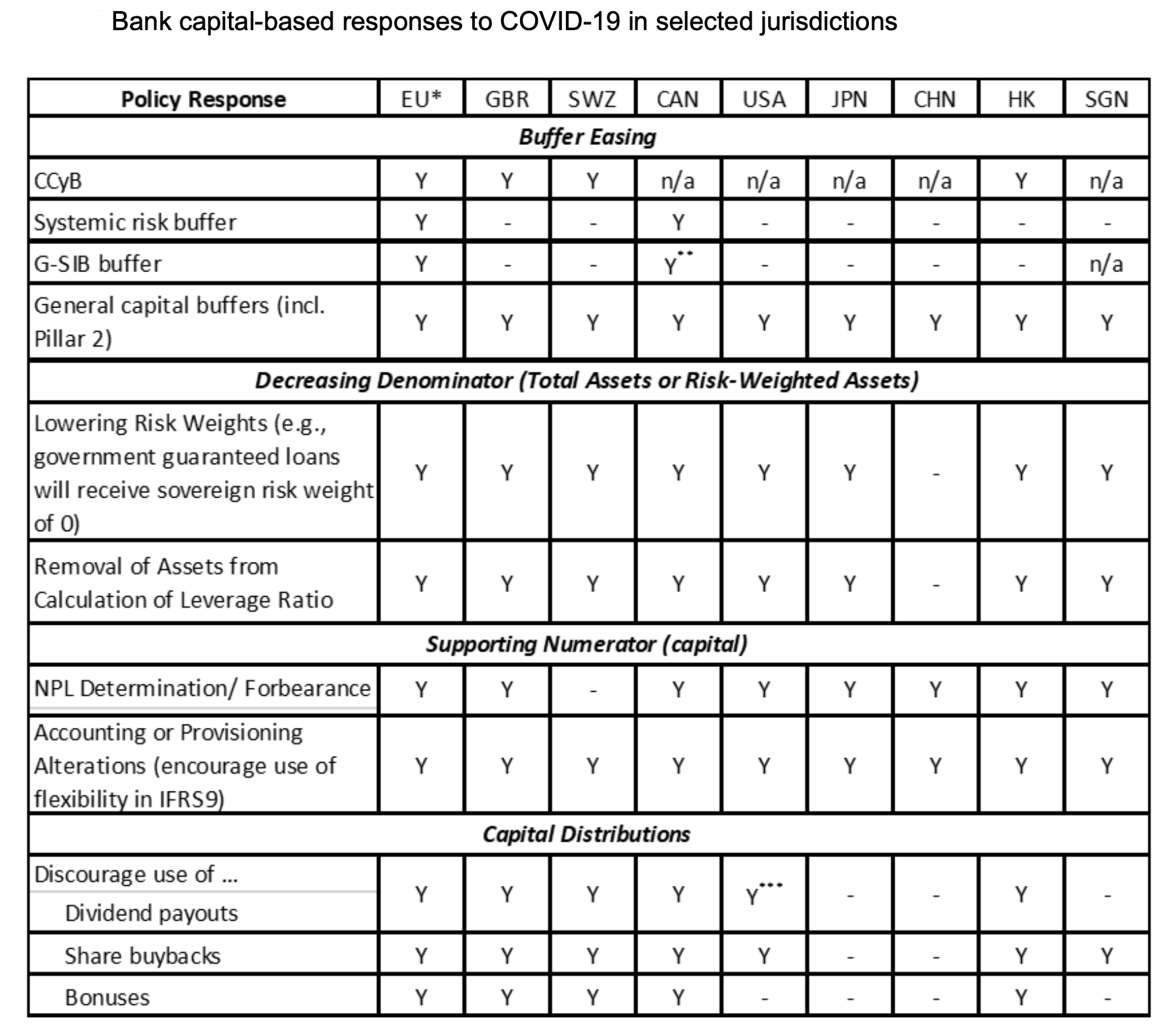

The COVID-19 induced “Great Lockdown” has cast doubt on the efficacy of bank buffers in supporting the real economy in times of crisis. Despite accommodative regulatory and supervisory action, banks remain hesitant to draw on their buffers to maintain credit provision. Recognising the difficulty in judging the demand for credit in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, this column focuses on the potential supply of credit and explores the obstacles to “usability” of bank capital. It concludes that the current capital framework falls short: there is not enough “usable capital”, and the disincentives to actually draw it down are too strong. Finally, it recommends improvements in current capital framework to overcome these issues.